A recent report on US courts reveals that many are lagging behind the private sector in AI adoption, and some don’t allow AI use at all. This could mean a missed opportunity to trim case backlogs and establish a stronger operational architecture

Just as generative AI (GenAI) is making inroads into private law and tax practices and corporations, so too is it making an impact on the public legal sector, especially within the nation’s court system. Indeed, the rise of AI and GenAI is expected to be the most impactful trend for courts currently, with 55% of survey respondents saying they believe it will have a transformative or high impact on their work, according to a recent survey of US courts from the Thomson Reuters Institute (TRI) and the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) AI Policy Consortium for Law and Courts.

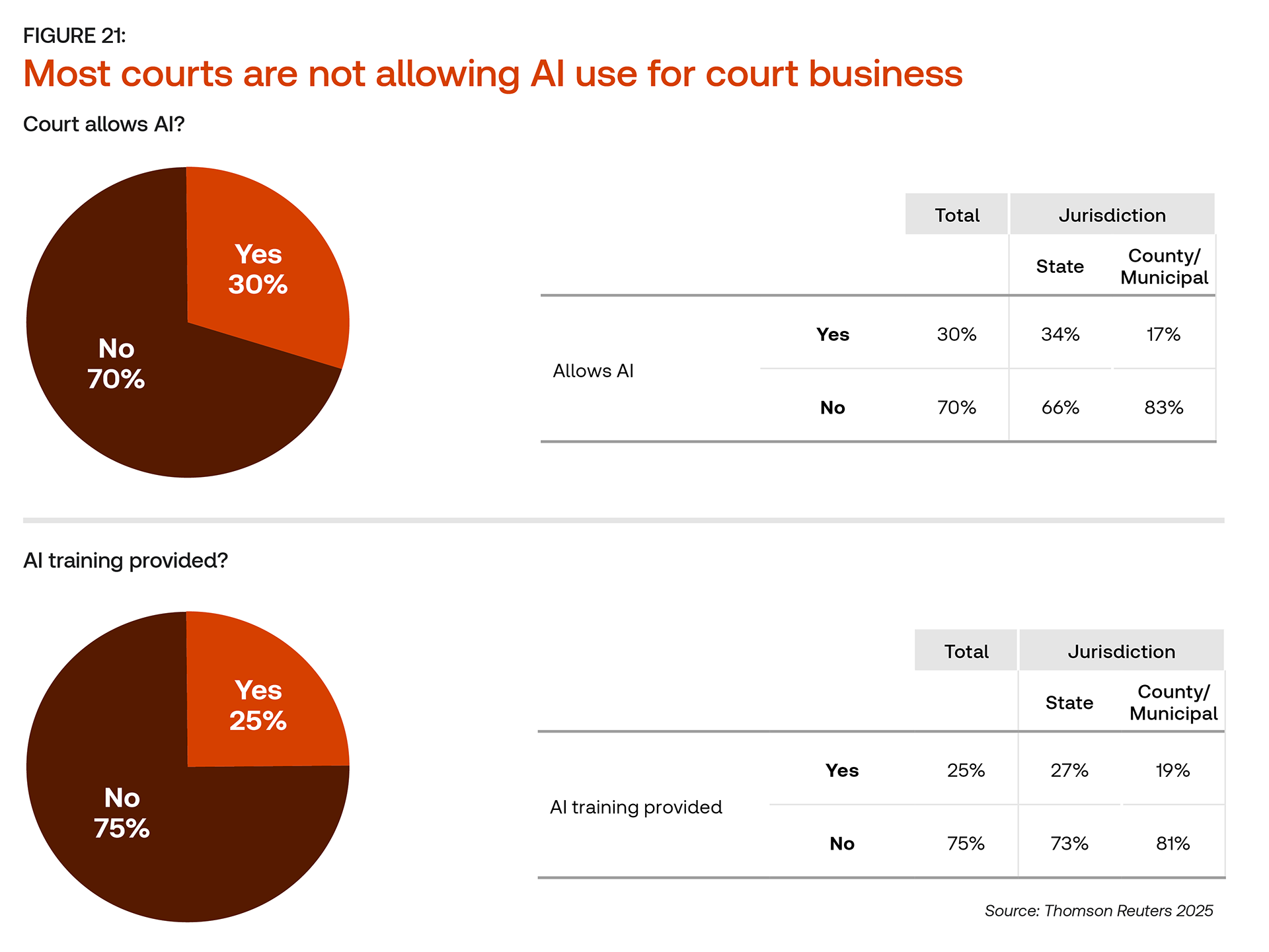

Even though higher caseloads and delays abound, the survey found that courts are lagging behind other areas of the law in actually understanding and adopting advanced technology. The majority of courts surveyed still do not allow AI use for court business, with concerns around overreliance on technology and malicious use of AI still among top concerns. There also remains a lack of court personnel to actually institute the technology, and many courts expect decreases in their IT and technology budgets.

Unfortunately, this represents a potential missed opportunity for courts, given how many judges and court personnel want to tackle the ongoing problems of case delays and backlogs. GenAI, after all, is squarely designed to perform low-level, repeatable tasks in order to save time for court personnel. However, reluctance to even allow the technology into courtrooms, let alone embrace it, may cause courts to become disconnected from the private law attorneys who already are integrating the tool into their daily work.

“Overall, I think the GenAI’s integration into all areas of professional life is inevitable,” one US senior law clerk told TRI. “Courts have an opportunity to embrace the technology where it can be used, but I know that many judges will take convincing before adopting the technology.”

The state of AI limbo

Although some courts are looking to adopt GenAI, few have actually done so as of now. As it currently stands, just 17% of respondents said their courts have instituted any sort of GenAI, while an additional 17% said their courts plan to do so within the next 12 months.

For some courts, the barriers to adoption may be structural. About two-thirds of courts experienced staff shortages in the last year, after all, and 30% expect their IT and technology budgets to decrease within the next 12 months, according to respondents. Further, some courts may simply not have the bandwidth to onboard GenAI in an enterprise way — an especially difficult task for a new technology that takes time and care to properly implement.

Register now for The Emerging Technology and Generative AI Forum, a cutting-edge conference that will explore the latest advancements in GenAI and their potential to revolutionize legal and tax practices

Yet even for those court professionals looking to use AI or GenAI on an individual basis, some courts may have barriers that are more cultural. In fact, GenAI may not only be discouraged within many courts, but it also may be outright banned. According to the report, more than two-thirds of respondents said that AI is not allowed for court business — and for county/municipal courts, that figure rises to more than 80%. Few courts also provide any sort of training around AI to their court workers.

The reasons as to why largely breaks down into two distinct categories. When asked what potential negative consequences of AI they are most worried about, more than one-third of respondents cited overreliance on technology, which could possibly diminish attorney reasoning and skills. “There’s an unfortunate likelihood that it will surpass what it should be — a drafting and inspiration tool — and become a shoddy substitute for thinking,” said one state court law clerk.

Additionally, one-quarter of respondents pointed to the potential for AI to be used maliciously, such as with counterfeit orders or falsely created evidence. This mirrors findings from the TRI’s Generative AI in Professional Services Report, in which respondents highlighted hallucinations and GenAI’s general accuracy as one of their major barriers for adoption.

The problem many courts may run into, however, is how quickly AI is being integrated into tools that they do use on a daily basis. More than 80% of respondents to the courts report said their courts use case management, document management and e-filing systems — most of which use some element of AI to categorize and sort documents, and are rapidly scaling GenAI capabilities to ask questions of case documents, summarize case documents, and create timelines of cases, among other features. Similar features are present within data analytics and reporting technologies, document automation technologies, and many back office administrative technologies — all of which are used in more than half of courts.

As a result, courts may find themselves stuck. The legal world — as well as the legal technology tools courts regularly use — are rapidly moving towards GenAI, becoming a regular part of their daily work in some fashion. Judges will be facing these technologies sooner rather than later, and if courts don’t change their regulations and overall posture towards AI and GenAI, they risk being left behind and without the opportunity to shape the future of technology in the legal profession.

A chance for leadership

Indeed, as the report illustrates, there remains an opportunity for courts to be leaders in this space both for internal operations and for the legal world at large. Externally, courts are regularly asked to provide guidance about emerging topic areas, and GenAI is no exception. By educating themselves about the practical opportunities and challenges of GenAI, judges and court personnel can better work with the private sector to establish boundaries around acceptable AI usage in courtrooms.

“There is no doubt its use will increase,” said one US court attorney. “So, there needs to be strong processes and controls applied to the generative process itself regarding ethical obligations and accuracy, and to setting parameters within the legal system in which it will be acceptable.”

Even within internal court operations, however, there remains an opportunity for growth. Only about half of court professionals say they have enough time to do their jobs, according to the report, with respondents saying they desire more time to work on case preparation and management, legal research, and even doing their actual jobs. When asked what they would do if more time were available, one respondent simply said: “I would just spend more time doing everything.”

Respondents who have used AI and GenAI recognize there is an opportunity here. Even with the slow pace of AI adoption generally across court systems, current active users estimate saving 2.8 hours per week over the next year. In three years, they estimate that figure to grow to nearly 6 hours per week, and in eight years to nearly 9 hours per week.

These figures are estimates, of course, and assume both technology advancements as well as wider court adoption. However, there are many areas in which technology can help courts today — and as Judge Scott Schlegel of Louisiana’s Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal recently told TRI’s Clarity podcast, there remain a lot of initiatives that courts could tackle easily through technology. And the time to start building that architecture is now.

“There are so many things out there that we need to get to before the shiny new object, which is GenAI — but that’s not to say we should ignore it,” Judge Schlegel said. “There are so many things we could do today that are low-cost, low-hanging fruit that will not only impact the justice system overnight but will form the building blocks that we can properly layer GenAI on top of it.”

You can access a full copy of the Staffing, Operations and Technology: A 2025 survey of State Courts from the TRI and NCSC AI Policy Consortium for Law and Courts here