The use of GenAI in the courts has the potential to address some concerns, like efficiency and transparency, and can even lead to better outcomes overall; yet it’s important to assess the challenges as well

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools offer promising opportunities for courts and legal professionals to advance fair and efficient case resolution, offering the opportunity to improve customer service, aid self-represented litigants, automate legal research, address staffing shortages, and assist judges in sentencing. Additionally, these tools can make judicial records more accessible to the public and the media.

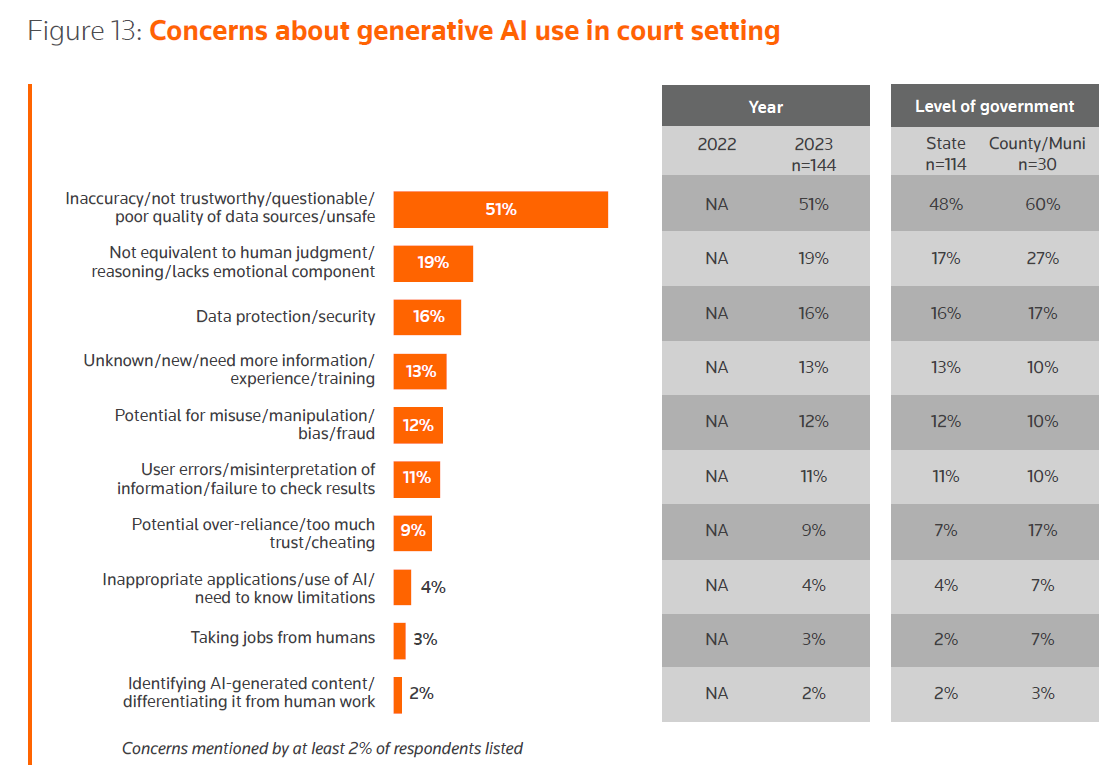

Yet, this integration of AI-driven technology faces skepticism, according to the Thomson Reuters Institute’s 2024 State of the Courts report, which showed that more than half of the judges and court professionals (51%) surveyed for the report shared concerns about the accuracy and quality of data sources tied to AI-driven tools, as well as concerns over preserving human judgment in the justice system (19%).

Not surprisingly, some courts are issuing new guidelines on AI usage as cases of misuse emerge. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (Louisiana), for example, issued a proposed rule governing the use of AI in November 2023, requiring certification that AI tools were not used, and when they are used, requiring certification that citations were reviewed for accuracy. This follows the appearance of hallucinated citations (fictitious citations generated by AI tools) that had been included in appellate briefs.

The Florida Bar’s ethics committee also released a proposed opinion suggested that lawyers should obtain permission from clients before disclosing confidential client information to third-party AI tools, as well as making recommendations on oversight best practices. And an opinion issued by the West Virginia Judicial Investigation Commission reminds judges that they must be aware of the influence of AI in their lives and never use AI tools to reach a conclusion on the outcome of a case.

Ensuring accountability with AI tools

While some, like Judge Scott Schlegel of Louisiana’s Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal, have advocated for court modernization, there’s skepticism about using AI tools to guide judicial decision-making. However, there are ways to harness AI’s potential without compromising public trust. The Texas Judicial Branch argues, for instance, that AI tools can be used for the benefit of litigants through the development of litigant self-help portals and for providing legal training to community members. Legal practitioners and judges can also benefit from the use of AI tools to analyze past case histories and rulings to better tailor their own orders, motions, and briefs. Judges could also consider recent trends in establishing bail or sentences.

Particularly concerning are the evidentiary concerns of the use of AI in the courtroom, highlighted by an increase of deepfakes, or AI-generated fake (yet highly believable) images or videos. The American Bar Association (ABA) hosted a presentation on the impact of deepfakes and their outsized impact on jurors. Indeed, jurors who hear oral and video testimony are 650% more likely to retain that information and tend to align their perceptions with what they have seen, even if they are aware that the presented evidence could be fake, according to the presentation.

Rules of evidence, as they are currently written, require that evidence be relevant, but not necessarily authentic. The Hon. Paul Grimm, retired U.S. District Judge for the District of Maryland, suggests that judges schedule hearings to dispute the authenticity of evidence well before jurors ever see potential deepfakes.

Addressing workforce shortages & transparency in courts

As more courts across the country face staff shortages, states are looking to modernize their technology and reevaluate their workforce requirements. California courts struggle to hire court reporters and often find their hands are tied from using voice writers or electronic recordings for many cases. Court reporters can require up to six years of training and must pass rigorous certification exams, while voice writers can be trained in less than two years.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (Florida) utilizes digital reporters to monitor audio recordings of proceedings and produce official written transcripts. Digital reporters can work remotely and can oversee several courtrooms simultaneously. Matt Benefiel, Trial Court Administrator for the Ninth Circuit, says that he feels speech-to-text AI software tools aren’t yet the equivalent of the human ear. In fact, automatic speech recognition programs are prone to errors when multiple defendants share a microphone, are more likely to inappropriately transcribe non-white speakers, and can inadvertently capture private sidebar conversations. Currently, use of speech-to-text software still requires human review, annotation, and at times, redaction.

Indeed, the US judicial system has been called to task by some for its lack of transparency compared to other branches of government. PACER, the federal court’s public access service tool, charges the public to view records online, and the revenue generated from the tool comprises about 2% of the federal judiciary’s budget, or more than $145 million in 2019. By comparison, many executive and legislative federal agencies provide free access to their records online. Legislative efforts to broaden free access to court records have stalled, most recently in 2022.

Leaders in academia and technology have developed their own open-source tools to use AI technology to extract such information from court datasets. For example, groups at the University of Oregon and Stanford University used AI to extract information from transcripts of parole hearings; and SCALES Open Knowledge Network (OKN), a collaborative academic research project led by Northwestern University, has used AI to analyze a range of datapoints across district courts. (Their datasets can be analyzed by district court, and they have made their code available for open-source use by others.)

Data analysis can lead to better outcomes

Georgia State University, a partner in the SCALES-OKN work with Northwestern, was awarded a $1.5 million award from the National Science Foundation in 2023 to develop an integrated justice platform. The proposed platform will use AI tools to connect and share criminal justice data across data silos in the states of Washington and Georgia with a goal of reaching better client-centered outcomes. A smaller-scale program was launched in the Los Angeles County Public Defender’s Office in 2023, which digitized and organized more than 150 million court records. By analyzing such rich datasets that include immigration history, mental health status, prior convictions, military service, and more, attorneys can help advocate for defendants and connect them to social programs as a diversion to incarceration.

In short, while judicial hesitancy around AI tools remains present, these concerns do not excuse the judiciary from remaining vigilant in understanding these tools and their impacts. While the judicial process may prefer to remain human-centric in the present, AI tools are showing that they can improve court participant experiences, judicial outcomes, and increase transparency within the judicial system.