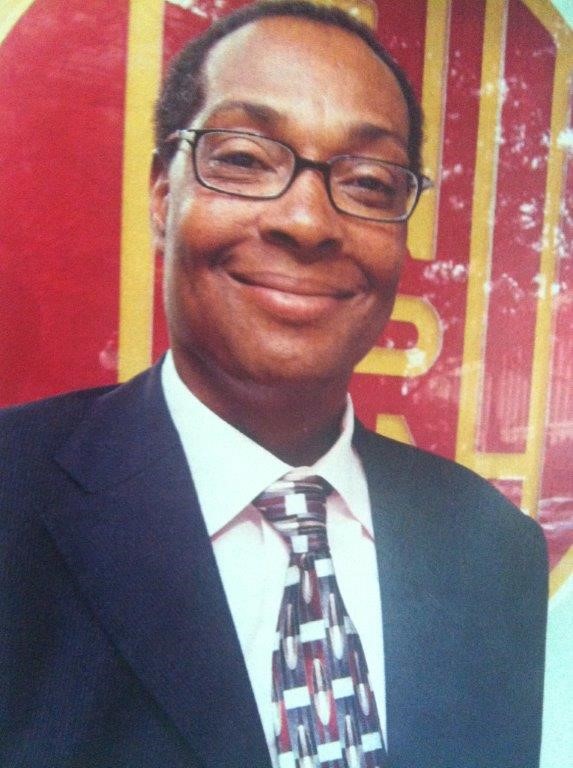

Ron Jordan, who has been in the diversity recruiting business within the legal industry for over 25 years, explains how legal employers can attract attorneys of color

As part of the Legal Executive Institute’s Next Gen Leadership: Advancing Lawyers of Color, we sat down with Ron Jordan, Senior Principal Director at Carter-White & Shaw, an executive talent search firm for diverse attorneys for law firms, in-house legal departments and lobbying firms. He has been in the diversity recruiting business within the legal industry for more than 25 years.

Legal Executive Institute: What is the best way for legal employers to attract potential candidates of color?

Ron Jordan: The best way is to recruit at historically black law schools and within affinity law student groups at majority schools. I make the case by pointing out those who graduated from these schools and are renowned for their legal brilliance — Thurgood Marshall, Constance Motely, Vernon Jordan, former Governor Douglas Wilder, the first African-American governor of Virginia. All of these accomplished lawyers graduated from Howard University Law School.

Employers should also recruit candidates at the top of graduating classes at the perceived second-tier schools. In New York City, the law schools that come to mind are Fordham, Pace, Quinnipiac, and Benjamin Cardozo. In North Carolina, Marshall and North Carolina Central Law School are two that pop up in my mind, and they are located in the heart of the Research Triangle.

I make the case for these schools because of the fact that each one carries the chip-on-the-shoulder mentality, a positive trait for lawyers. In my experience, the majority of law students of color saw within their young lives, a wrong that they knew could be righted by knowing the law, thus law school.

Legal Executive Institute: In your work, where do you see bias in the recruiting model and processes of legal employers? At the entry level ranks? For lateral candidates?

Ron Jordan: The greatest bias within entry-level ranks are the people who are leading the first-round interviews. For the most part in on-campus recruiting, they are younger white women. It is my opinion that, when one wants to recruit, train and retain, it would be smart to have those whose job is to recruit — who may not be lawyers — be more similar to those that you are trying to recruit.

There also seems to be a problem with many firms to wait until the law student of color is in law school. I think about the football or sports college drafts, no one in the NFL or NBA is recruiting from just colleges anymore. Many innovative teams are keeping track of high school students.

I realize that law firms don’t have the deep pockets to keep track of the best high school students of color but law firms can be more aware of colleges and the many schools where their current attorneys of color attended, as well as the law schools they graduated from. To illustrate, I spoke to a black associate the other day currently with an Am Law 100 firm on the East Coast. He attended Emory, which is a very good school and has graduated a number of well-respected law students of color. He mentioned his current firm found him by attending the national and regional Black Law Students Association conference. He first saw them there, and the firm had a booth each of the years he attended Emory. He was impressed that the firm had a black equity partner as its head of diversity. He was impressed to find lawyers of color from his school were in attendance at the booth. He is now happy to recruit and tell his story about his experience at the firm.

It seems so simple to use the resources that are in the firms’ backyards instead of “going to the same wells (aka schools) and hoping that they fill up with talent after their competitors have drawn all the water (talent) from the well.” Law firms are hired for their innovation and ingenuity within the confines of certain parameters or restrictions of the law. Though when trying to recruit, retain and promote attorneys of color, especially black attorneys, they lose whatever made them successful with non-diverse attorneys and don’t go the extra miles to win.

Legal Executive Institute: Where should legal organizations go to recruit attorneys of color?

Ron Jordan: Be resourceful and look at other schools and organizations where law students of color gather, such as Bars of Color, national conferences and regional meetings. Each year, the Bars of Color have mid-year and national conferences. Each year law students of color have national and mid-year conferences. Law firms that have even a few attorneys of color should at least show respect to those in the firm and recruit from their law schools.

The bias lies in doing the same things over and over, which is the definition of insanity. I respect lawyers for their resourcefulness, except when it comes to the hiring attorneys of color and most notably, black lawyers.

Legal Executive Institute: What are your recommendations for changes to candidate selection, interviewing, and on-boarding to remove these biases?

Ron Jordan: Diversify who does the recruiting and interviewing beyond white men and women. Insert recruiters that are people of color. If a firm doesn’t have someone in the ranks in recruiting, train a person of color internally who sees that they would be a greater help.

Law firms have a tendency to only look at the firm’s recruiters and the firm’s lawyers. I am of the mind that rank and file employees are a great resource in pointing out talent in their communities. The involvement of line employees of color accomplishes two things: i) the person is actively ensuring their own employment and helping the firm’s bottom line; and ii) the person is encouraging young college and high school students to attend law school.

To illustrate, I was visiting a firm in a major Mid-Atlantic city. My visit was to talk about diversity and inclusion in recruiting. The receptionist was a long-time employee of the firm, and her firm only had a few attorneys of color. She was quite candid in asking me to state my business. I told her I was there to increase diverse attorneys at the firm. In response, she discussed how the firm relies on her to talk with potential and current clients and to pay attention to the details. She stated: “I make sure that each call is delivered without fail to the appropriate attorney or administrator. I have worked here for more than 25 years, and I am known within the black community in this town. I don’t understand why my employer doesn’t ask me to help them recruit young black college and law students who may come here on my recommendation. Instead, they are paying you to do what I would do for free.”

I am not trying not to get paid for my services, but she is right. Law firms and in-house counsel don’t use their line employees. Many of them have a vested interest in their communities in knowing where the intellectual talent lies.

Legal Executive Institute: What are some of the challenges that legal employers will face in putting your recommendations into action? And what actions do you recommend to overcome them?

Ron Jordan: Blowback comes from those attorneys and administrators who don’t like change, which is ironic in that the legal business is changing, not only in terms of the law but also in mannerisms and attitudes. Many items that were status quo many years ago don’t fly today. Sexism, racism, and prejudice were practiced openly and without consequences in business across our nation. Business has changed more rapidly than law firms and much of why law firms have not changed is because their paymasters — their corporate law department clients — aren’t demanding change, like Kim Rivera at HP, Don Liu at Target, and countless other diverse and non-diverse general counsel are doing.

I was once told by a GC that they didn’t want to dictate how their outside counsel ran their firms — didn’t want to “look under the hood” was the analogy the GC used. But that made no sense. If a GC wants to have diverse attorneys of color working on your matters, that means impacting how your outside counsel firms hire, retain, and promote their attorneys of color.