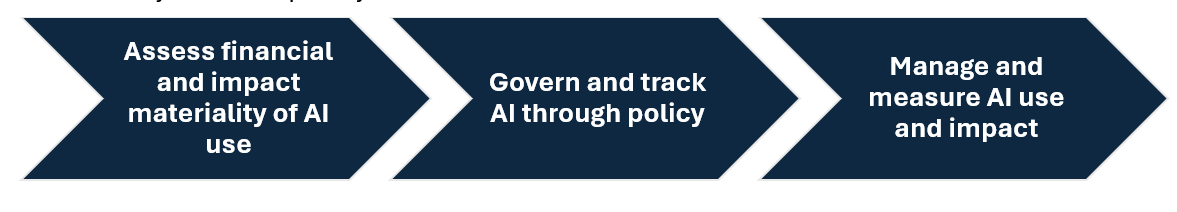

As AI use increases, governance of environmental implications increasingly depends on embedding AI into materiality assessments, measurement practices, and reporting systems

Key highlights:

-

-

-

Treat AI use as a material sustainability driver — Bring AI explicitly into financial materiality and impact assessments so you can see where AI changes the scale or severity of existing issues or introduces new risks or opportunities.

-

Map, measure, and baseline AI demand to make it governable — Create an inventory of in which situations or how often AI is used and establish utilization metrics over time so you can spot growth, redundancy, and hotspots.

-

Control AI impact through policy, oversight, and supplier expectations — Set rules for appropriate AI use and triggers for extra review before scaling AI, and manage impacts whether AI is in-house or provided by vendors.

-

-

While AI clearly already is changing how companies operate and deliver, it’s also demanding changes in how sustainability systems are designed and governed. Indeed, much focus to date has been on the environmental impact of AI’s energy use, water consumption, and supply chain challenges.

Yet, there is another side to consider that involves examining how AI itself is used within organizations. It is important to understand where AI is applied throughout an organization, how often it is used, and whether those uses are necessary — and most crucially, how and when the review processes is applied. By including AI in materiality assessments, a clear track is set for its deployment, with systems in place to address any environmental and social impacts and risks that arise before they become problems.

To ensure effective value creation of AI use, organizational leaders need to focus beyond the footprint, by mapping their AI use, defining control and review processes, developing systems for ongoing quantification, and reporting transparently. The goal is to manage AI’s impact from the inside out, making sure the benefits are worth the risks and that sustainability remains a priority.

Bringing AI use into materiality and impact assessments

Financial materiality and impact assessments provide a practical basis for governing AI through the structured process of identifying and prioritizing significant impacts. Many sustainability topics influenced by AI use — including energy demand, emissions, water use, and workforce effects — are already assessed in existing materiality exercises. What is often missing is an explicit examination of how AI alters the drivers of those impacts.

The International Sustainability Standards Board’s IFRS materiality guidance centers on financial materiality, which is defined by whether a topic could reasonably be expected to influence the decisions of investors or other users of financial statements. How AI is used within companies undoubtedly influences the risks and opportunities the company faces and certainly can affect a company’s financial position.

Early closures aligned with the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) suggest that AI is typically addressed within broader topics such as workforce impacts, digital governance, or business conduct rather than identified as a standalone source of dependencies, impacts, risks, and opportunities. This reflects the difficulty of assessing impacts that are indirect, cumulative, and demand-driven, and topics in which regulations and best practices are still evolving.

Bringing AI into materiality assessments requires assessing whether its use alters the scale or severity of existing impacts, introduces new risks and opportunities, or creates dependencies that warrant prioritization.

In practice, determination of the materiality of AI hinges on understanding scale and concentration — such as in which situations it is used or embedded in critical workflows and the scale of applications across functions, tools, and systems. Mapping AI use across use cases and delivery models can help provide the basis for determining in which instances AI meaningfully alters environmental, social, or financial exposure.

Once these priority areas are identified, organizations then can move from qualitative assessment to structured oversight by establishing a baseline for AI utilization and its associated potential impacts.

Governing AI demand through policy

Once a basis of materiality for AI is determined, the next governance step is to shift towards control, primarily through policy that’s supported by proportionate measurement of demand.

As access to AI expands, it can become a default tool for routine tasks, increasing demand through duplication and persistent use cases without sufficient oversight or challenge. Policies then can set expectations for appropriate application, conditions to assess depth relative to task value, and crucially, what conditions should trigger additional review before AI is scaled or embedded into core work processes.

Quantification underscores these policies by making AI use visible over time and by tracking its impact. For most organizations, the starting point for measuring AI impact is obtaining a consistent view of utilization and its evolution. This determination of scale will then later support the precise attribution of energy or emissions. Comparing precise indicators to utilization will enable leaders to establish a baseline and then support effective identification of growth, potential redundancy, and overall impact.

Managing AI’s impact

Where organizations own or operate their own AI infrastructure, management responsibility will sit within established operational controls, including decarbonization of electricity supply, managing cooling water use, and overseeing hardware lifecycles, such as refurbishment, reuse, and recycling. Governance also explicitly needs to cover model training and retraining, especially in areas in which concentrated energy and water demand can arise. In fact, it should be subject to planning and review rather than treated as a purely technical decision.

Where AI capability is accessed through external or third-party providers, these same impact areas must be addressed through policy and a rollout of supplier engagement practices that link disclosure with procurement decision-making. Management without direct control necessitates setting expectations and engaging external providers on energy sourcing, water stewardship, hardware management, and transparency around model training practices and associated impacts.

Governing AI as an impact on sustainability

AI’s sustainability effects depend on infrastructure efficiency, energy sources, and governance of its use in organizations. That means that effective management must include assessing material impacts, setting policies for demand and monitoring, measuring results, and making transparent reporting.

Treating AI as a source of managed sustainability can better help mitigate risks and ensure that the environmental and social effects of AI use are aligned with value creation.