The work of public relations and marketing companies, acting as "reputation launderers" to unsavory clients, can offer those clients ways to avoid notoriety and evade sanctions

Reputation launderers, particularly public relations and law firms, and their role in promulgating disinformation increasingly are hindering sanctions and financial-crime compliance teams’ ability to conduct enhanced due diligence and make accurate judgments about the risks that certain customers pose, according to policymakers and researchers.

The services such professionals provide can permit kleptocrats, oligarchs, and politically exposed persons (PEP) to layer their wealth into Western economies where it is difficult for compliance staff and law enforcement to detect and, ultimately, to disentangle any illicit transactions.

Reputation laundering is a growing industry of lawyers, accountants, public relations firms, and image consultants that guide and advise kleptocratic actors and PEPs through a process of rebranding, transforming them from despot to debutante. Often this process involves giving large sums to charities, universities, and political parties, buying citizenship through golden visa schemes, inviting politicians onto their company boards, as well as placing flattering articles about themselves in showcase publications.

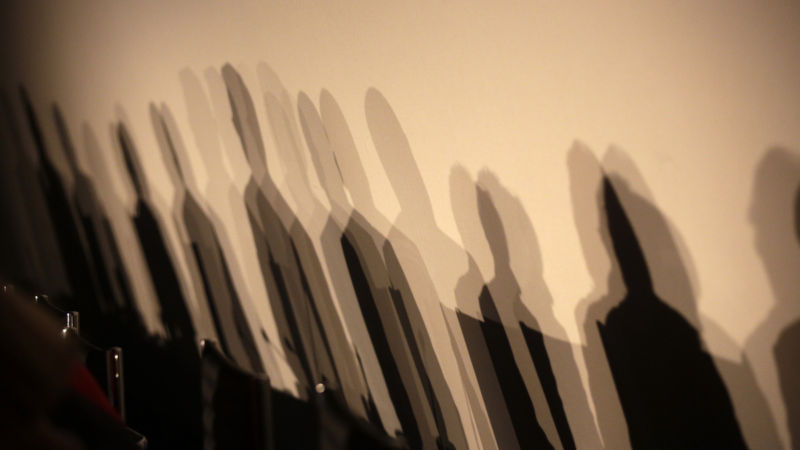

Such public relations and marketing companies, operating behind the scenes, offer their clients a shield against accusations and notoriety, officials said.

“It is this rebranding of an unsavory past that is the essence of reputation laundering. By minimizing and obscuring evidence of corruption and authoritarianism in their home country, reputation laundering enables kleptocrats to enjoy their spoils freely around the world,” wrote Tena Prelec, a research fellow at the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford in March. “It also allows authoritarian governments to manipulate public perception, sometimes even by undermining the functioning elected representatives in national and international institutions.”

That ability to manipulate public perception by sowing social media with disinformation, and to create a plausible deniability over sources of tainted wealth, distorts these actors’ sanctions and financial crime risk profile. Once reputation launderers have transformed their clients’ social and business image, it is difficult for compliance professionals to differentiate between legitimate and illegitimate activity, or to effectively screen for negative news.

While London has come under fire as a haven for kleptocrats, academic research and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists‘ Pandora Papers show that such enabling activity is common, with the United States, France, and Portugal among the countries leading the offerings of reputational laundering services. Governments have been slow to address the enabler problem, and enforcement bodies lack the staffing and resource to enforce the rules that do exist, officials said.

Disabling enablers

Lawmakers internationally have been reluctant to clamp down on kleptocrats’ enablers despite increasing concerns about the influence these individuals and their enablers wield in the spread of disinformation aimed at undermining democracies and justifying Russia’s war in Ukraine.

The United States is among the less than 10% of countries that are non-compliant with Recommendation 22 from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), making the US one of 11 nations that do not require enablers to look out and report dirty money, said Josh Rudolph, fellow for malign finance at the Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD) at the German Marshall Fund think tank.

In October, the US Congress introduced a bill called the Establishing New Authorities for Business Laundering and Enabling Risks to Security Act (the ENABLERS Act) that would force lawyers, trust companies, real estate brokers, accountants, art and collectibles dealers, public relations firms, and third-party payment service providers to conduct due diligence on the sources of funds.

For the ENABLERS Act bill to be passed into law, legislators must overcome stiff resistance from what Rudolph calls the Four Horsemen: the legal profession, company formation agents, accountants, as well as covert public relations and marketing companies, whose skills can be hired in the service of reputation laundering.

“Legal professionals are the single-most important enabler sector to regulate because they are the most useful to oligarchs and kleptocrats looking to secretly funnel dirty money through law firms’ bank accounts,” Rudolph told the UK’s Royal United Services Institute. “Lawyers are the most obstinate and organized group in their resistance to [anti-money laundering] AML rules. The American Bar Association (ABA) has spent a quarter century in this war of attrition with the FATF.” The legislative strategy surrounding passing the ENABLERS Act has to be very carefully thought out, Rudolph added, including at the stage of scoping the statutory language. “This bill will do is important and has to be accompanied by political strategies to divide and conquer the ABA.”

It will be important to track this legislative initiative, because if Congress fails to pass such legislation, the US Treasury cannot address these enablers. It would instead be forced into playing “small ball” perhaps by repealing some of the enabler exemptions in the previously passed Bank Secrecy Act, Rudolph said.