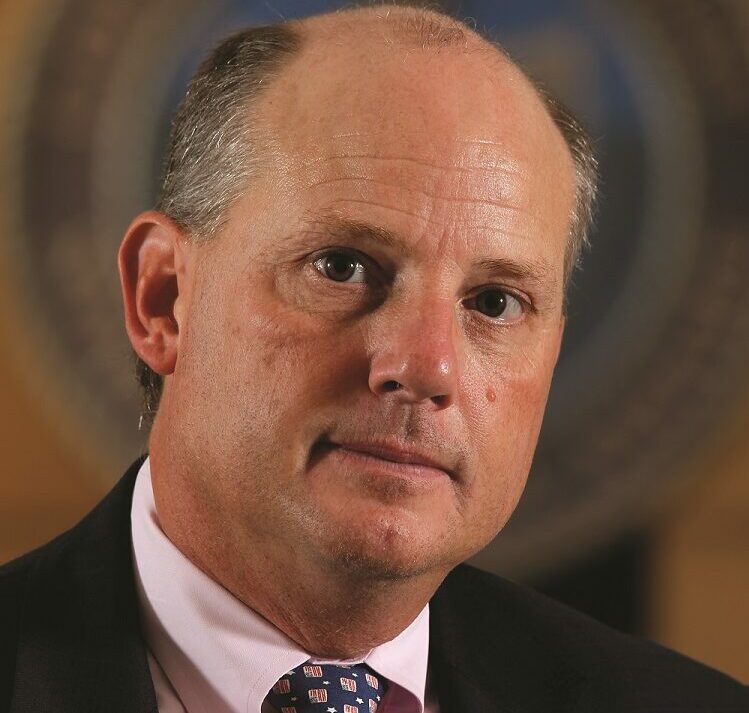

Leo E. Strine, Jr., former Chief Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court, points out the need for corporate boards to better manage the polarization of ESG within their organization

Companies’ need to address environmental, social & governance (ESG) risks and obligations has become even more essential for business sustainability in a year in which there has been a profound shift towards a new reality marked by increased unpredictability, according to the Thomson Reuters Institute’s recent 2023 State of Corporate ESG report.

Yet, opponents of ESG initiatives remain vocal. In many instances, this puts companies in a difficult spot because they are caught between the political forces leading the ESG opposition and what many stakeholders — including employees, investors, consumers, customers, among others — want. Indeed, we’ve highlighted potential solutions on how to approach those with pro- and anti-ESG viewpoints from using stakeholder mapping on divisive issues, to focusing on individual issues that fall underneath the ESG umbrella because they are less polarizing than the term ESG.

Leo E. Strine, Jr., Of Counsel at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz and former Chief Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court, offers pragmatic advice for corporate boards to manage the polarization of ESG. Through the lens of good corporate citizenship, Strine’s guidance draws on shared assumptions across the political spectrum about the place of corporations in society. “Corporations play a unique role in society,” Strine explains. “They capture the dynamism of the marketplace and create wealth for our society. At the same time, corporations have dangers. They are powerful and larger than any individual human being. Therefore, as members of the public, we want them to follow the rules of society and make money ‘the right way’.”

More specifically, Strine emphasizes that there is common ground in how society wants companies to act, despite the varying political beliefs of Americans. Among others, Strine highlights these:

-

-

- companies need to treat their workers well and compensate workers with wages and benefits that allow them to live a better life for the benefit of their families; and

- organizations should pay their fair share of taxes and support the communities, charities, and school systems in which they operate.

-

Board leadership is essential

Strine also offers practical guidance on what companies need to do to remain out of the fray across the politicized environment of ESG. Specifically, Strine’s key point is for company boards of directors to employ stricter guardrails that are similar to those used in corporate governance practices when there is the potential for conflicts of interests between corporate managers and the company’s stakeholders. These include:

Ensure board approval of any corporate positions on political or social issues — Make sure that any stances on these issues are explained by reference to the company and its stakeholders. Strine urges caution for companies when taking stances about political issues that do not involve a direct connection to the company’s business, that are matters of equal concern to all Americans, and where Americans are divided. When that is the case, the company’s stakeholders are also likely to be divided, and that is part of the reality of a free society. Thus, he suggests that corporations that take stands be able to explain why doing so was of value to the company’s stockholders, workforce and customers, and that the board as a whole deliberate on and stand behind the decision, and endeavor to consider how the decision will affect and be received by the company’s stakeholders.

Equally important is to make clear that whenever the board does take positions, there is not an expectation that employees have to agree; and as a corporation, it is a priority for employees with a spectrum of viewpoints to feel welcome to work and that the same is true for the company’s consumers. Likewise, Strine says that when companies take a considered policy position on a controversial issue, they have to be consistent or look hypocritical. “Many companies have lost credibility because they have spoken out on public issues like voting rights, reproductive choice, and climate change, and then have been found to have given millions of dollars to the political interests on the other sides of those issues,” Strine notes.

Avoid political contributions that are not authorized by stockholders — In the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision — which struck down the law prohibiting corporations and unions from making political contributions in connection with federal elections — Jack Bogle, founder and former CEO of Vanguard, employed the rule that “the corporation shall make no political contributions without the approval of the holders of at least 75% of its shares outstanding.” For Strine, the recommendation is no contributions at all because companies don’t have stockholders’ money for political purposes, but if they are to be made, they must be under a stockholder-approved plan.

Strine also advises that corporate directors set a policy that the company only donates through a political action committee, that independent directors monitor and approve all donations, and that no political donations are made to candidates whose views do not accord with the company’s stated policies and values. These are important to avoid the hypocrisy of the company taking a stand on an issue while at the same time, in hindsight, discovering that company funds were given to candidates who supported the opposing side. “My advice to company boards is to state up front that, the board must give direction on where the funds go and how they are used, and request that they have to be consistent with company values,” he states, adding that companies should use the rule, “When in doubt, don’t give,” to avoid the appearance of hypocrisy.

Corporate political spending directed toward partisan committees of any kind needs to be eliminated, according to Strine. Instead, he suggests companies “give political contributions to nonpartisan organizations, including the National Governors Association, the National Conference of State Legislatures, and/or the National Association of Attorneys General and underscore that the company welcomes the opportunity to provide funding to organizations that are bipartisan and focus on making our Republic stronger.”

Emphasize diversity of thought and belief

Boards could reduce the pressure on corporate leaders by taking the view that politics is properly left to the company’s employees and consumers because the organization desires to be a company that respects diversity in all ways, including the diversity of thought and belief, which is at the heart of a free society, according to Strine. A corporation taking positions on issues that do not have any direct connection to its business, over which it has no unique control, and of which there is no likelihood for across-the-board consensus among its investors, employees, and customers could potentially put the company in a shaky spot.

Indeed, companies with employees from varying backgrounds who come together through a common goal and shared values in the workplace to see colleagues, communities, and families do well is a noble goal in and of itself. “We sometimes lose perspective in the minutia that we have far more in common than we do differences,” Strine states. “We lose sight of the fact that operating with respect in an effort of good faith and tolerance, that people coming from different ethnic backgrounds and from a varying spectrum of political persuasions is what makes our organizations and our Republic strong.”