At the recent CodeX FutureLaw conference, one hot topic was "computational contracts" which the legal industry is now exploring with increasing interest

The bleeding edge of the legal industry is now building interfaces at the intersection of code and law through computational contracts.

These computational contracts (sometime called smart contracts), according to Stanford University, are a universal Contract Definition Language that will allow terms and conditions to be represented in machine-understandable way. As a result, computers will be able to process and reason over the contracts automatically with a guaranteed degree of accuracy. The Stanford project sees this as not only a significant reduction of legal transaction costs, but it also opens a variety of new options to create better contracts.

With these building blocks taking shape, we can finally peer into how technology will guide legal into a fundamental paradigm shift around legal contracts. This idea, among others, were discussed and debated at the recent CodeX FutureLaw 2021 conference, held virtually.

Before the legal pyrotechnics on self-executing contracts, the conference began in more of a reflective state. Thomas Kim, Chief Legal Officer and Company Secretary at Thomson Reuters, spoke about the industry transformations ahead, emphasizing the intelligent, thoughtful adoption of new technologies. In crafting his message, Kim focused his attention on the compelling need to establish industry standards around technology, where companies must create global values. Pivoting to regulation, which he believes will ramp up, Kim explained that is vitally necessary for companies and their technology to weave a fair fabric of social consciousness and awareness.

Finally, Kim described the key principles around artificial intelligence which Thomson Reuters has offered to the industry, prioritizing safety, security, privacy, and humanity.

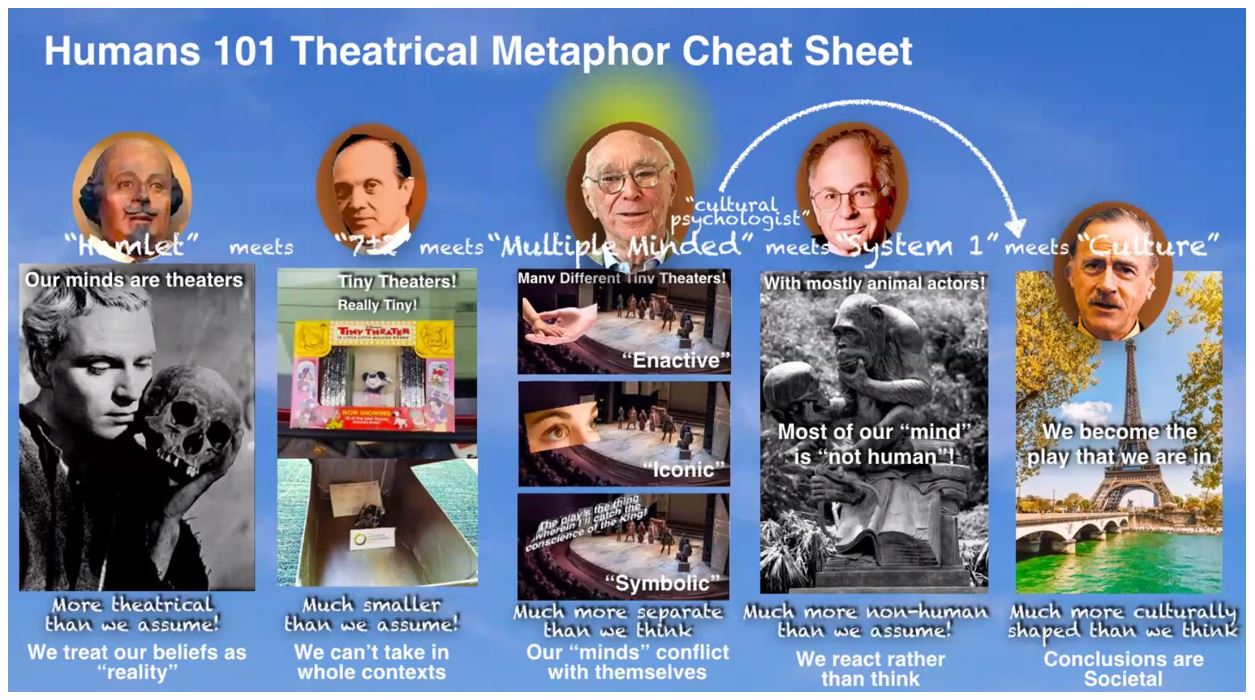

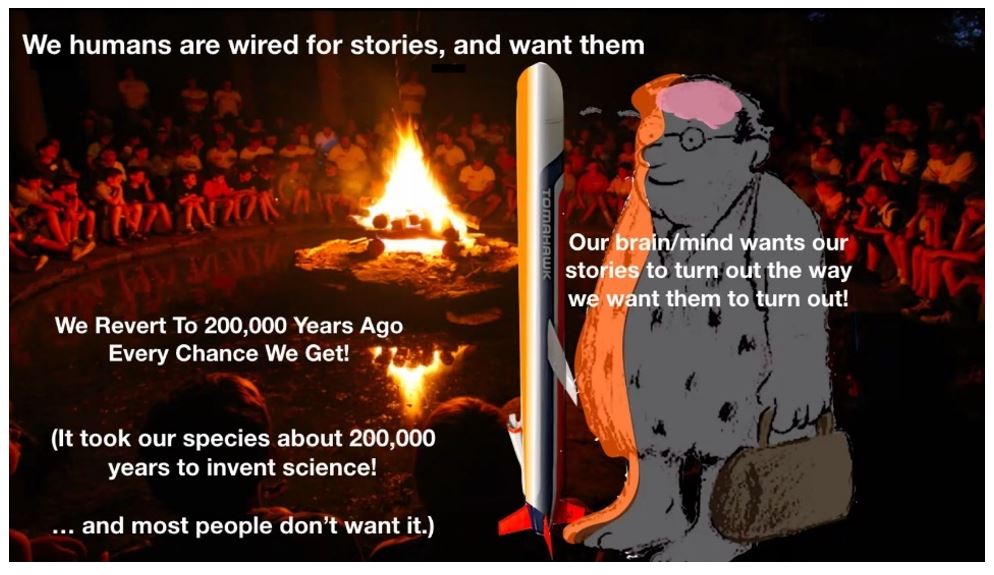

In another session, Allen Kay, a preeminent American computer scientists and Turing Award Laureate, led an eccentric yet nuanced keynote on intellectual curiosity and bias. He purposefully quizzed the audience, asking: “With so many bright people on the Supreme Court, why do we have such different opinions?” Utilizing theatrical metaphor throughout, he unpacked a theory of human perspective, with the theater in our minds. “Humans are easily fooled, want to be fooled, pay to be fooled, fool ourselves, and we pay to fool others,” Kay said, adding that most of our mind is still operating on instinct from 200,000 years ago.

Kay’s incisive vision on the human condition laid out the inherent concerns surrounding the next era of computational power and the biases built into them. Our malleable minds can be shaped by those in power with their narrative, he surmised, and without the legal industry applying critical thought, the producer of the play will create a scene in their own vision, i.e. bias within the code for the legal industry.

Forming the law into computational contracts

The conference then shifted to the concept of computational contracts covered by two different panels, which both were in near uniform agreement that we are going to see serious disruption to the contractual components of legal agreements in the near future.

Harry Surden, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Colorado, moderated the panel and described the complexity of helping computers understand the English language, which is no easy feat. Michael Genesereth, professor in the Computer Science Department at Stanford University, then began with a premise that we need to rethink how contracts are written, stating that there’s a need to “form the law into computable contracts.”

To do so, however, first we have to create a domain ontology, which is the first vocabularies and vernacular that can be used to describe a universe of the legal discourse. In this instance, we are referring to dependencies between types of knowledge in legal reasoning. It sounds easy, right?

One surprising theme the panel offered was the interstitial nature of using AI to convert contract language to a form of computational contracts. “We are currently trying to rebuild the horse out of metal and machines rather than progressing to the car,” said Oliver Goodenough, Law Research Professor, University of Vermont. Instead, he said, we will get to a point where we need to rethink the contract itself and then code around it.

What panelists proposed was a system that used the ontology of a legal system, coupled with interdependencies and outside data to build a dynamic contract. Eventually, this would be a no-code solution that would be akin to the WYSIWYG (What you see is what you get) web pages that people build today, rather than using HTML.

The second panel focused on computational contracts by using the insurance industry as a backdrop. Michael Pieciak, Commissioner of the Vermont Department of Financial Regulation, described what computational contracts look like, noting these contracts are so rich in technology that it took a 122-page report to describe the algorithm they use for insurance underwriting.

Roland Scharrer, Group Chief Data & Emerging Technology Officer at AXA, described the complexity of what his company has built and how it works, adding that contract creators can get insights from data within the industry and then write the contracts. “This technology is real and being used now,” Scharrer said.

Panelists also observed that in the not too distant future, the contracts will be more complex, and users will be able to leverage external data with the contract itself. Eventually, the contract will be able to execute itself. We also will see an increase in the use of decentralization components, which is being embraced by the FinTech, eCommerce and insurance industries.

While sessions touched on automation and disruption, the binding element which connected all of the day’s debate was a focus on creating a more equitable, open, and fair legal landscape imbued with thoughtful, unbiased technology. Reflecting on the keynote, it’s fair to surmise that the opportunity is immense — yet, we must commit to critical thinking, challenging traditional norms, and re-conceptualizing how technology can enable access to justice and better legal services for all.