For law firms today, measuring productivity by hours-worked is vital at the moment, but dependence on that metric may be ripe for a change

There is an argument to be made that law firms have poorly defined productivity as a metric for almost as long as they’ve used it. Productivity is typically defined as the number of billable hours a lawyer works (or perhaps more appropriately, the number of hours the lawyer enters into billing) in a given time period. In this sense, it’s not really so much a metric about how much work the lawyer has done, but rather a measure of how much time the lawyer spent doing it.

I’ve written before about the conundrum of lawyer productivity as a measure of inputs rather than outputs, which is a more typical view of productivity among businesses. Now, however, the advent of generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI) and its myriad potential implications for how legal work is done, requires a reexamination of the definition of lawyer productivity.

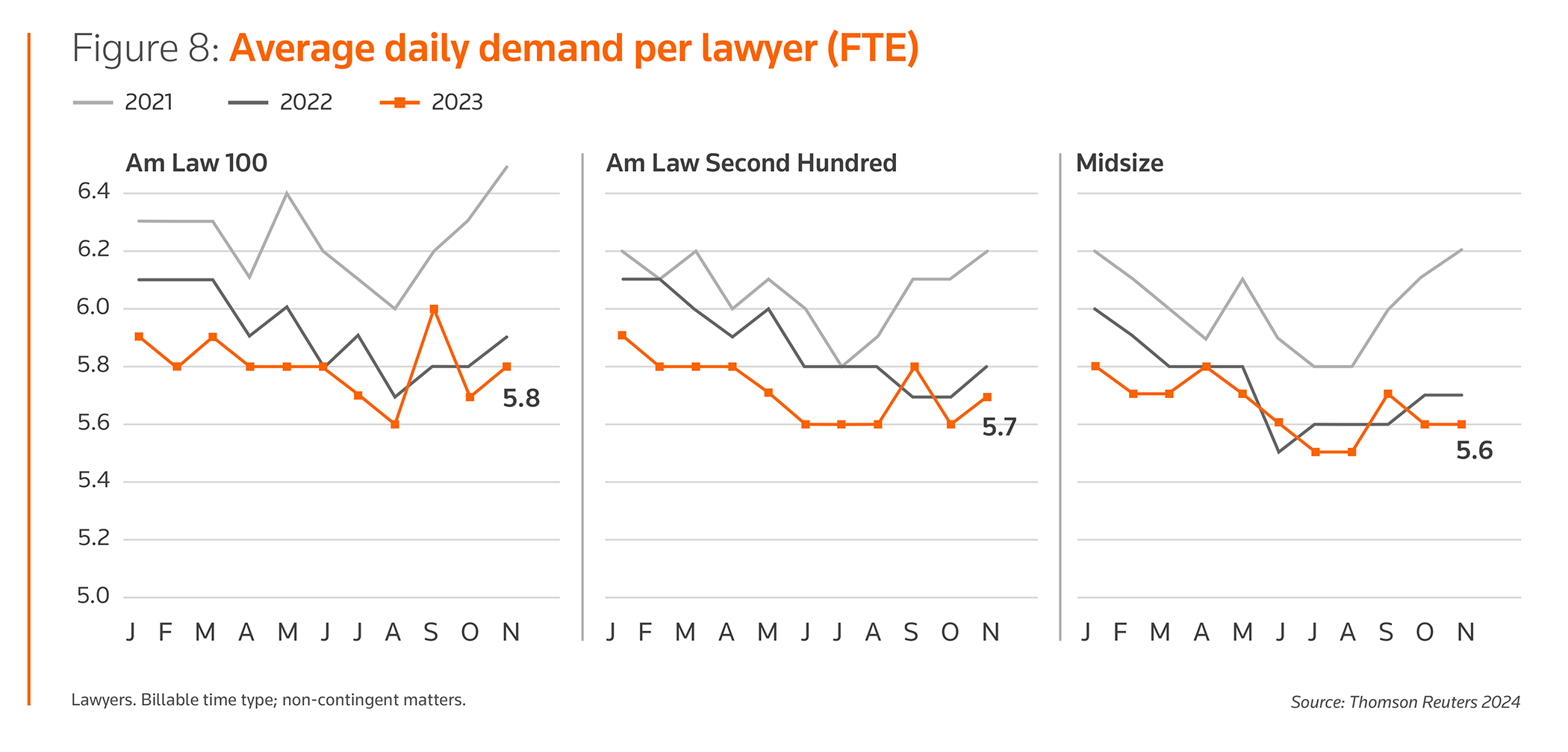

In the most recent Report on the State of the US Legal Market, we looked at a more discrete measure of lawyer productivity than has been featured in past reports. Rather than looking at lawyer productivity as a measure of hours per lawyer per month, we instead showed a metric called average daily demand — essentially, the average number of hours put into billing by the average lawyer on a daily basis. By this measure, no segment of law firms we’ve tracked managed to even match, let alone surpass, the average daily demand figure for 2022, and each law firm segment was dramatically behind their 2021 figures.

With the potential benefits that Gen AI may hold for improving work efficiency, particularly around more repetitive tasks, the question arises: Might 2021 have been the last peak for the billable hour as a key metric?

To be sure, there has been a plethora of pieces in the legal press (including on this blog) over the years predicting the “death of the billable hour.” I’m not so much talking about the billable hour’s demise as its relegation.

The full impact of Gen AI remains to be seen, but given the number of proponents and innovators driving it forward, the idea that it will have little to no impact on the delivery of legal services seems unlikely. While Gen AI may never replace an experienced attorney’s judgment in negotiating a transaction or drafting a legal pleading, it will almost certainly replace hours that lawyers currently dedicate to tasks like research, cite checking, and perhaps even brainstorming to a certain extent.

Replacing rote tasks

These types of innovations aren’t new. When I was a clerk at the Minnesota Court of Appeals, standard practice was for all cite checks to be done in the books in the law library, a painfully time-consuming process. Today, every lawyer has access to tools right in their word processing software that will perform the same cite-checking tasks instantaneously. Technology has essentially fully replaced an essential but low-value task. Examining a typical lawyer’s workday today, it is not hard to compile a list of other potential tasks, both legal and administrative, that are ripe for the same sort of replacement.

While increasingly disallowed by clients’ own outside counsel guidelines, rote tasks still account for an appreciable portion of the average lawyer’s billable hours, particularly for associates. As those tasks are replaced by AI-driven innovation, the hours will similarly disappear. So, this raises another question: Will lawyers be able to find new tasks to fill those now-vacant hours, thereby buoying the current productivity metric, or will the market need to look for an alternative metric to more accurately capture the legal work being completed?

Shifting the concept of productivity towards tasks-completed and away from a reliance on hours-entered seems appropriate, if not overdue. Certainly, some types of work and even some matter types like litigation will still be largely viewed through the lens of hours worked. Even within those categories, however, there will be examples of work that will be more properly valued by the fact that such tasks were completed, rather than by how long it took to complete them.

The myopic view of attorney productivity as solely a function of hours-input needs to be revisited. It likely will not be replaced by one single metric, but rather by a combination of metrics that more accurately reflect the actual work being done. Time spent arguing in court or negotiating a deal will continue to be valuable in its own right, of course; but in contrast, time spent drafting or proofing documents will likely diminish as AI steps up to take on more of a role.

And ultimately, the better measure for a lawyer will become not how much time was spent doing a task, but rather, how much the lawyer’s efforts contributed to the prosperity of the firm and the benefit of the client. Exactly what metrics should take the place of today’s measure of productivity is likely something we’ll be exploring much more throughout 2024.