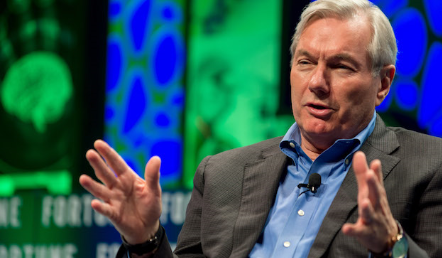

Much of what infectious-disease expert Dr. Michael Osterholm has to say about the COVID-19 pandemic is not what U.S. citizens want to hear — cases and deaths are climbing; people don’t understand the dangers (or worse, don’t care); federal leadership is a joke; a vaccine may or may not work; herd immunity is unrealistic; and the worst is yet to come.

Osterholm is the director of the Center for Infectious Disease & Policy at the University of Minnesota, and for decades has been regarded as one of the world’s leading public-health experts. He jokingly refers to himself as “Bad News Mike,” because he has spent most of his professional career warning governments and the public about the dangers of a runaway pandemic.

True to his nickname, during a recent Thomson Reuters AI Invited Speakers Series event, The Covid-19 Pandemic: The Evolving Reality, Osterholm reiterated his much-publicized assertion that the next six to twelve weeks are going to be the “darkest” days of the pandemic. If current trends continue, he says, “the U.S. could see as many as 500,000 to 800,000 deaths by spring.”

Again, not exactly what people want to hear.

A battle plan for survival

Despite the gloom and doom, however, Osterholm also insists it is important for Americans to understand that all is not lost, and that another narrative — what he calls “finding hope in the middle of the tunnel” — needs to penetrate the fog of coronavirus confusion and fatigue. After all, vaccines are being developed, therapeutics are improving, scientists have more virus data and medical technology at their fingertips than ever before, and people can do plenty to protect themselves and their loved ones (masks, social distancing, etc.).

More importantly, Osterholm and other public-health experts already know how to control the virus and open up the economy, even without a vaccine. In fact, the last chapter of Osterholm’s 2017 book, Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs, contains a detailed “Battle Plan for Survival,” in which he lays out a coordinated science and policy approach for fighting global pandemics that he has been warning for years are “inevitable.”

“You can do both — health and the economy — at the same time. It’s not magic or pixie dust,” Osterholm insists. “If you bring the virus under control, it will also have major implications for the economy.”

He cites Melbourne, Australia as an example of a city that saw cases spike in July, then implemented tight restrictions and contract tracing that reduced new cases to zero by late October, laying the groundwork there for an economic recovery. Many other Asian-Pacific countries — such as New Zealand, Vietnam, Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea — have had success with similar protocols, Osterholm observes, and none of them resorted to the sort of authoritarian tactics used in China.

Restoring public trust

When it comes to fighting the virus, however, the big difference between other relatively successful democratic countries and the U.S. is the level of trust people have in their government and its leadership, says Osterholm. “You have to have a government whose leadership is such that the population will follow that leadership,” he says, because without public trust and cooperation, you basically end up where the U.S. is now — divided and confused.

In the U.S., “half of the population doesn’t want to take a vaccine” because of safety concerns and fears that the scientific process is being politicized, he says. “In communities of color and among indigenous populations, the distrust of vaccines is incredible,” he notes. “In some inner-city populations, 70% to 80% of the people are unwilling to take a vaccine right now out of fear of being used as guinea pigs.”

To combat this growing skepticism and rebuild trust in government, the U.S. needs to start telling itself a different story, Osterholm says — one that’s based on honesty, science, and leadership. “What we need right now is an FDR, someone to provide us with a vision of what is coming, not sugarcoat it, and at the same time give hope” by articulating a plan and telling people what they can actually do, he explains. “Right now, we don’t have that, and we’re not really understanding what the challenges are.”

The challenges ahead

One of the biggest challenges in America, of course, is convincing a large swath of the population to take the coronavirus more seriously. Osterholm laments the politicization of the virus, and says there will always be skeptics, but insists it’s essential for Americans to find a way to unify themselves in the fight against COVID-19, or suffer the consequences.

“Part of the challenge is helping everyone realize that it’s us vs. the virus, not us vs. them,” Osterholm says. “Right now, we’re telling a story about how angry we are at each other, and how the virus is a hoax. These are key messages we need to deal with.”

According to Osterholm, another major problem is that science can tell societies a great deal about the virus and how to eradicate it, but science doesn’t help much if it doesn’t inform intelligent public policy or change the public’s attitude toward the dangers of COVID-19. “We far too often take all these statistics and all this information and put it together to write wonderful reports with lots of color, but it doesn’t make a damn bit of difference if it doesn’t change people’s behavior,” he says.

Likewise, if and when a vaccine is approved, data science and artificial intelligence will be essential tools for tracking the efficacy of the vaccine as it is administered to the public, Osterholm agrees. But what if the data doesn’t tell us what we want it to? What if it turns out to be impossible to go back to the degree of safety to which we’ve become accustomed?

“I can’t tell you what’s going to happen in the spring and summer, but if this vaccine only has a limited impact on our society, we really are going to have to re-evaluate how we live life every day in public places,” Osterholm says. That means re-thinking the need for offices and buildings, how people work, the role of essential workers, policy approaches to public safety, and how societies support their citizenry’s emotional and economic well-being, he says. And for professionals, it means a prolonged period of uncertainty and, possibly, opportunity.

“I think this is going to be one of the most tumultuous periods of time for how we do business in the world,” Osterholm says. “How do we redefine that?”

Simple, ruthless little viruses

Whatever happens in the coming year, Osterholm says he hopes the world’s experience with COVID-19 will result in some “humility” about the power of microbes to disrupt human life.

“These are simple little viruses. They’re not bullets. They’re not bombs. They’re not computer viruses. They’re just plain viruses, and look at what they do to us,” Osterholm says. “I think we can all agree that we don’t want to have these pandemics overlayed on our society, because they are ruthless, they are economically painful, and they challenge the very nature of who we are as humans.”

And by the way, this won’t be the last coronavirus we have to deal with, Osterholm reminds us. Simply raising billions of chickens and pigs to meet the protein needs of the planet’s eight billion inhabitants is enough to keep the pandemic cycle going, he says. “These are rich conditions for the spread of viruses, so we’re going to see more of these events, not less.”

If and when the COVID-19 crisis is contained, Osterholm says the bigger question will be, “How are we going to prepare for what’s coming next?”